Any ideas?

Any ideas? Reducing Risk

- Avoiding general anaesthesia through regional techniques

- Use of propofol infusion for general anaesthesia

- Avoidance of nitrous oxide

- Avoidance of volatile anaesthetics

- Minimisation of perioperative opioids

- Adequate hydration

Other than the recommendations to avoid volatile anaesthetics and minimise intraoperative opioids (which are strength A2), these all have a grade A1 level of recommendation. The absolute impact of these interventions is a little bit harder to unpick, though it is probably clear from the risk ratios described in the first post how avoiding the risk factors might work, with many of the recommendations being fairly obvious.

They do outline the impact of some of the strategies that they describe though. Of note, the incidence of PONV is around 9 times less in patient receiving regional rather than general anaesthetic. In addition, for those that do require general anaesthesia, the use of total intravenous anaesthesia (TIVA) reduced the incidence of PONV by 25% in one study, with an NNT of 5 in another study. Not bad.

Their description of the impact of nitrous oxide on PONV is limited to just a couple of lines, noting some increased risk but that this was probably limited in low risk patients. This is something I hope to have a look at in the next post though (which I have found pretty interesting) so if you’re not using nitrous due to its emetic effect, keep your eyes peeled..

Antiemetic Prophylaxis

I’ll make one exception to this by having a look at ondansetron which they described as the ‘gold-standard’ antiemetic by which the others are compared (and fortunately the one I see used the most). They quote a NNT of 6 for preventing vomiting and NNT of 7 for preventing nausea and that it is best given at the end of surgery. With regards to side effects, the NNH from a single dose is quoted as 36 for headache, 31 for liver enzyme derangement, and 23 for constipation. The risk of QT prolongation at doses less than 16mg is thought to be not significant, with a handful of case reports described where arrhythmias may have been attributed to its use.

Moving on, the general recommendations they make for prophylactic antiemetic use can be summarised as such (a more user friendly flow chart is presented in the paper itself):

- At the moment blanket prophylaxis isn’t recommended (though may become more so with cheaper generics becoming available).

- Each patient’s risk should be calculated based on the different patient, anaesthetic and surgical factors.

- Baseline risk factor reduction should be used where possible and the impact of both PONV and antiemetic side effects on the patient should be considered.

- If the PONV risk if low, a wait and see approach is advocated

- If the risk is medium, single or dual therapy prophylaxis should be used

- If the risk is high, more than 2 interventions should be employed

Anything Else

Finally, a point I found particularly interesting was the evidence behind propofol's antiemetic potential. I had previously thought that some of known antiemetic effect may have been attributable to the avoidance of volatile (e.g. in TIVA). However, sub-hypnotic doses have been demonstrated to be as effective as ondansetron for prevention and treatment of PONV. They describe the option of a small dose (20mg) for treating PONV in an environment with close monitoring when PONV is very problematic, the main downside being the short duration (reducing the conscious level of someone who is vomiting though…?).

Final Thoughts

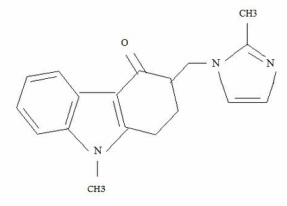

Thanks for reading and, as always, please let me know your thoughts on the topic (or any others). We shall hopefully have some more interesting posts heading this way shortly. And if anyone was still wondering, the picture is of ondansetron's molecular structure (couldn't find any other good ones is my excuse). Until next time...

Consensus Guidelines for the Management of PONV - Society for Ambulatory Anesthesia

Medscape - Prevention of PONV

APAGBI - Guidelines on preventing PONV in children (2009)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed