Getting it Right First Time

A lot of the data that GIRFT uses is drawn from data that are already collected; coding, the national hip fracture database, NELA, etc. This is supported by data that individual departments submit (which is quite extensive), and then analysed to look at what variation is occuring. The questions are then around whether this variation is likely to be relevant, and with the results subsequently being published both locally and nationally. A number of these reports have been undertaken already different surgical specialties nationally and are underway in some of the specialties we are most interested in: anaesthesia, perioperative medicine and critical care. As an example of the insights they may provide, the general surgical report shows variation in demand, activity, decision making and outcomes. These report allows comparison of local sites to their ‘peers’ across the country, making benchmarking possible, and potentially driving changing.

I find this use of data exciting, if not without a few slight concerns. Some of the changes that have already been implemented from such reports sounds very interesting, with changes to care structure (e.g. consultant triage) and adjustment of equipment use to impact on costs. My concerns, as were touched on in some of the Q&As at the end, would include problems with gaming the system, and the potential misapplication of findings. However, the approach is described as constructive rather than accusatory, and indeed it seems very valuable to identify areas for potential improvement as well as areas of excellence. There is ongoing work on perioperative medicine, including in the Northwest, with a focus on the 3 strands of daycase surgery, enhanced recovery (major elective), and emergency surgery e.g. laparotomies, neck of femur fractures. It will be interesting to hear more about the results of this process in the near future.

Do Children Need Preop Assessment?

The Global Landscape of Airway Management

This led onto the importance of strategies to manage such problems, and the DAS can't intubtae, can't oxygenate (CICO) algorithm is another piece of work that I can barely imagine a world without. The current guideline (from 2015) was only the 2nd iteration, and yet is such a key piece of work. Despite the importance of the guidance there has been quite a bit of debate about the approach to front of neck access (FONA), with the scalpel vs needle question causing a fair degree of controversy. The use of ‘The Airway App’ seems to be a great project to gain valuable information on such rare events. Incidents of FONA from around the world can be reported through the app, and the details provided on the factors involved analysed to try and glean nuggets of invaluable information. You can read more about the findings in this review in Anaesthesia, with perhaps the most interesting finding being that the scalpel-bougie success rate was the highest.

This led onto the scoop of the day; the first presentation of the new DAS awake tracheal intubation guidelines! The purpose of this again links back to the findings of NAP4. Despite there often being an appropriate indication for awake intubation, this approach to securing the airway was underutilised. Now although traditionally this has been a fibreoptic approach, there has been the description of using a similar approach to facilitate awake intubation using videolaryngoscopy (as we covered in the NWAM blog). Although the complication and failure rates with such an approach are both low (around 1%) it is also a technique that is rarely used by many anaesthetists. Indeed, this was one of the arguments that Dr Andrew Smith has employed to advocate for the videolaryngoscope approach, noting that this is a tool that many anaesthetists are very familiar with. The goal of the new DAS guidance was therefore to bring together a document that could help clinicians have a clear approach that they could use, including support on managing potential challenges. The full document will be fully unveiled at WAMM at the start of November and will certainly be worth keeping an eye out for. Some key learning points that I took away included:

- Utilising nasal high flow oxygen can provide the well recognised benefits of the technique without actually getting in the way too much.

- Sedation is definitely not a substitute for adequate airway topicalisation.

- It’s difficult to see if there is any difference between a fibre-optic or videolaryngoscope technique.

An excellent keynote speech from @ProfEllenO on airway management. The new DAS awake intubation guidelines sound interesting #periopman19

— Thomas Heaton (@tomheaton88) October 4, 2019

Perioperative Optimisation of Antibiotics

Breakout Sessions

Here are some further interesting links on the topic:

AI for anaesthesia

Machine learning algorithm to predict hypotension

This is also a fascinating podcast on the topic

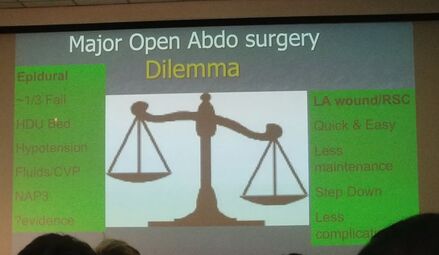

THoracic Epidurals

Dr Oliver Pratt led the charge for the pro side, focusing his argument along the lines of analgesia and outcome benefits. The evidence base is challenging, but epidurals have been convincing demonstrated as better than opioids (Cochrane 2016). In contrast, much of the work looking at the newer regional stuff has been non-inferiority, retrospective, or simply not comparing like with like. In addition, whilst not completely benign, NAP3 shows a decent safety profile. Certain other side effects, such as delayed return of GI function and respiratory complications, are better with epidurals, and ERAS still recommends their use. A problem then arises with the reducing use of this technique, as it is a skill that it is important to maintain and be proficient at to get the best results. If we move away from performing them regularly, it may become an area that we deskill in. A point of interest was when the question was asked at the end “as an anaesthetist, which would you rather have?”. For major abdominal incisions, the answer does still seem to be an epidural, although the final vote was only a 55 to 45 favour to the pro side (essentially unchanged from the initial vote). I think that that is the way that I would still lean, although it is reassuring to know that there are other decent options for pain relief in our armamatarium, which is never a bad thing.

These were some of the references that they used:

Cochrane: Epidurals vs systemic opioids.

Thoracic epidural anaesthesia.

NAP 3.

Rectus sheath catheters.

Tom

RSS Feed

RSS Feed