Spaced Repetition

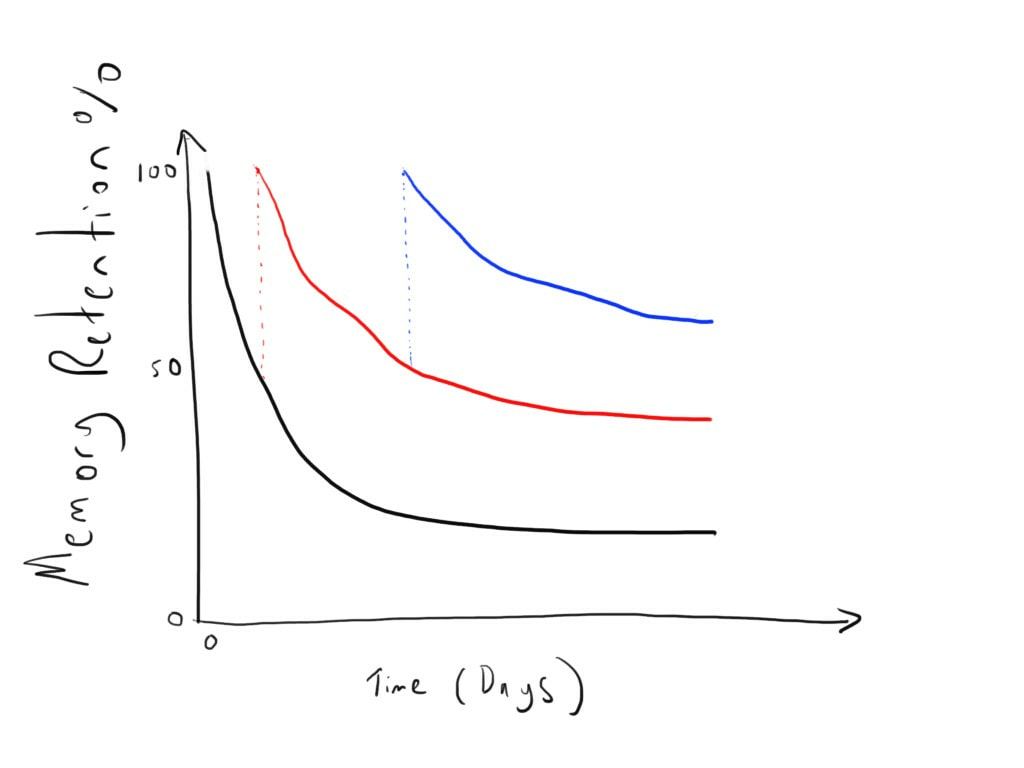

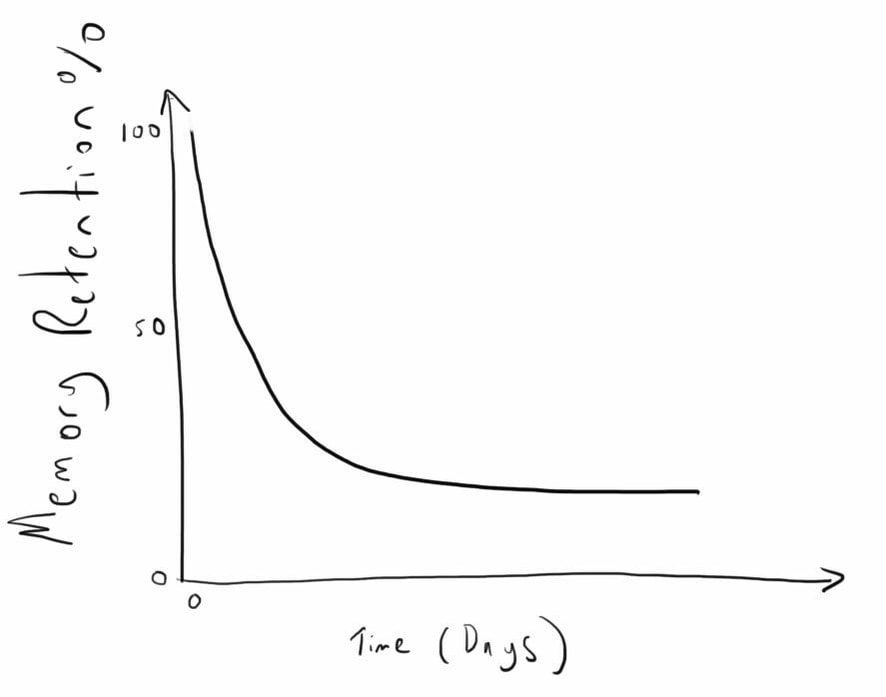

So now for the sale’s pitch, for just £9.99 a month, you can learn anything….just joking. As much as some of these benefits are impressive, I’m not quite peddling snake oil. The educational concepts behind spaced repetition are actually pretty ancient. The concept is this; when we learn something, it is surprisingly vulnerable to decay. Ebbinghaus famously described this effect by trying to remember random number, and the resulting graph bears his name (see below). The graph displays what happens to the knowledge that we have 'learned' during the period of time after initial learning.

Now there is another additional aspect of this which I often group together with spaced repetition - the testing effect. This is the observation that if you test yourself on a concept, you will retain it better than if you simply revise it. This even includes if you get it wrong, as long as there is timely correction. The trick seems to be that it needs to require some effort to get the benefit. As with the spacing mentioned above, if it is just on the edge of being forgotten, more mental effort is needed, it’s harder to do, but the consolidation into long term memory will be stronger. This is another nice video from the Osmosis team about the testing effect: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_wqG7g1kZUo

Putting it into Practice

As noted by Chris Nickson in his excellent blogpost on the subject, there are clearly some topics that it will work well for, and others it really won’t. To me this seems to centre around the degree of simplicity: the smaller the package of information to be recalled, the more effective this system. As such, remembering the dose of dantrolene is well suited, whilst the steps involved in performing an awake fibreoptic intubation might be less so. In my most recent Final FRCA exam preparation, there were a few ways that I felt it worked well:

- Definitions

- Categories

- Equations

- Graphs

- (Simple) anatomy e.g. brachial plexus line drawing

Why Bother?

The other argument is one of volume - there is probably a bit too much of this knowledge to constantly be looking up. This is probably the more applicable point for most of us. There genuinely is a lot of this stuff that we learn in exam preparation that is very useful (no I’m not looking at you trimetaphan) but just doesn’t get used with quite enough frequency to know well enough. Examples that I have come across this week include the different lung segments (I’ve been back doing some bronchoscopy after quite a gap), the definitions and normal values of the lung volumes/capacities (revising preoperative assessment of respiratory function) and the normal values of a ROTEM (was performed on a patient in theatre). It is these things that I feel I should know, and will benefit from knowing, but which will not stick in my memory without some concerted effort. As such, nearly all my learning now includes identifying components that I think I will want to consolidate into my memory, and creating simple question and answer cards for my Anki deck.

Does it Work?

Final Thoughts

BW

Tom

Links & References

- Osmosis. Spaced repetition. 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cVf38y07cfk

- Brown, P. Roediger III, H. McDaniel, M. Make it Stick: The Science of Successful Learning. 2014. The Belknap Press. Cambridge:Massachusetts.

- Nickson, C. Learning by spaced repetition. 2017. LITFL. https://lifeinthefastlane.com/learning-by-spaced-repetition/

- Anki. https://apps.ankiweb.net/

- Wyner, G. Fluent Forever. 2014. Harmony Books: New York.

- Schnapp, B. et al. Education theory made practical 2: Spaced repetition theory. ICE Blog. 2018. https://icenetblog.royalcollege.ca/2018/04/24/education-theory-made-practical-2-spaced-repetition-theory/

- Augustin, M. How to learn effectively at medical school: test yourself, learn actively, and repeat in intervals. Yale J Biol Med. 2014. 87(2):207-212. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4031794/

RSS Feed

RSS Feed