Adequate antibiotic admission prior to ICU admission in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock reduces hospital mortality

What did they do?

What did they find?

- Delay in ‘appropriate’ antibiotics until after ICU admission (the headline of the paper)

- Acutely sicker patients – Septic shock, higher APACHE II and SOFA scores.

- Chronically sicker patients – immunosuppression, cirrhosis, malignancy, age

A breakdown of the groups with different antibiotic timings provides a bit more information about what could be the important factors at play here. Of all the patients with a confirmed microbiological isolate the comparison shows that the group with a delay in receiving appropriate antibiotics until after ICU admission were more likely to have a hospital acquired infection and (probably related) a higher rate of ‘difficult to treat pathogens’. For me it is this breakdown that is probably most enlightening as to what this study is really showing, but there is a lot to be said about the causality etc. in such a study. However, it is interesting when it is noted that 98.3% of patients did receive some antibiotics before arriving on the ITU, suggesting that the delay wasn’t because nothing was given, rather that there were incidents when what they had wasn’t effective.

The other finding were rather less revolutionary, demonstrating that if you had features of a worse baseline (e.g. Cirrhosis, malignancy, immunosuppression) or severity of illness (septic shock, APACHE II score) then you were also more likely to day. There is probably a reason why they didn’t make the headline of the paper, but it always useful information to have.

Is it any good?

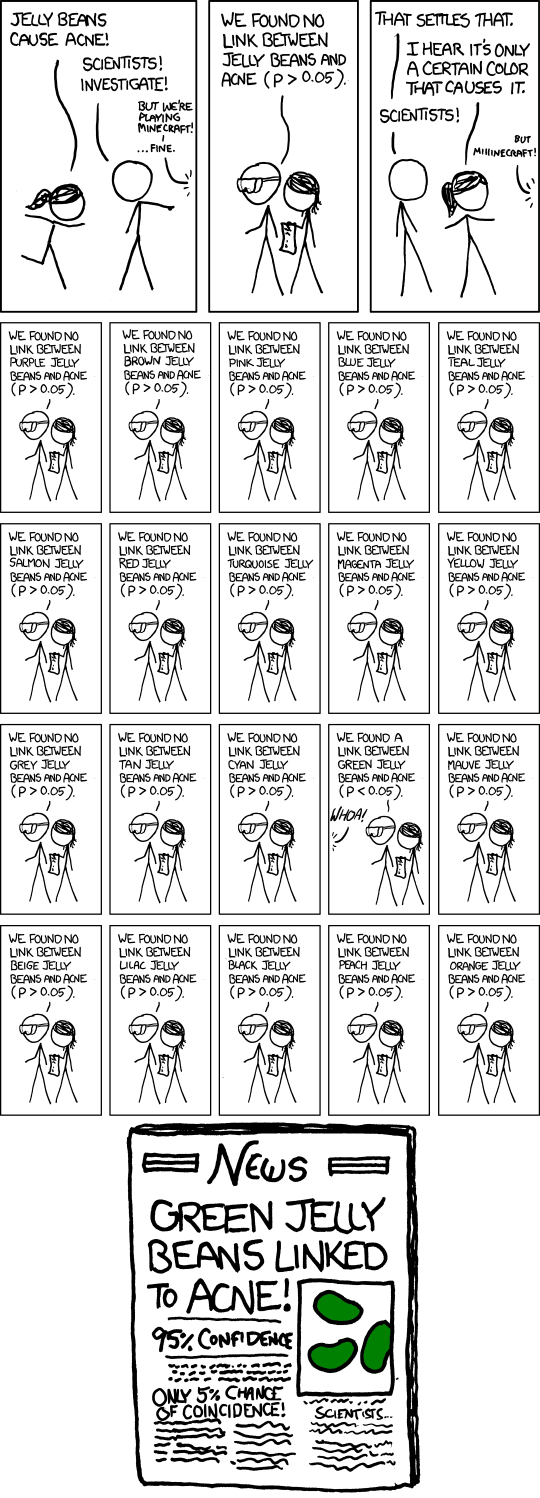

All this being said, the results demonstrated are fairly powerful and suggestive of sensible mechanism of actions in some regards. An absolute difference in hospital mortality of 20% is not trivial, and there would need to be some significant bias and confounding present to question such a result, especially as the number of patients is fairly decent. This is similar for a few of the other results that have cropped up with their multivariate analysis, such as the difference in ‘difficult to treat pathogens’, and they paint a rather nice picture of causality. There are certainly dangers in this approach to stats though (I think the cartoon from the excellent XKCD demonstrates it brilliantly).

Final Thoughts

So in summary:

- A delay in appropriate antibiotics increases hospital mortality

- There is probably an increased risk of this with difficult to treat pathogens (probably due to resistance to initial treatment) and this may be linked to the association with hospital acquired infections.

- Think carefully about what organisms you are treating when you reach for the antibiotics – that choice may significantly affect the patient’s chance of survival.

Tom Heaton

References

- Garnacho-Montero, J et al. Adequate antibiotic admission prior to ICU admission in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock reduces hospital mortality. Crit Care. 2015. 19(1): 302

- Kumar, A et al. Duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2006. 34: 15989-1596

Lower mage courtesy of XKCD.com

p.s. I would like to add my thanks to everyone that took part in our local journal club who made several contributions to the discussion that has led to this post.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed